John Arnold has made billions as an energy-trading phenom. But the rules of his game are about to change.

(Fortune Magazine) -- You could hear John Arnold trying to choose his words carefully. Seated at a conference table inside a drab government building in Washington, D.C., in August, Arnold hardly fit the stereotype of a swaggering, 35-year-old billionaire natural-gas trader.

He wrung his hands as he waited to speak and twisted his wedding band. He filled, and refilled, and re-refilled his water glass. Then he stuttered a bit before he gained momentum and politely advocated rules that would restrict others while allowing him to keep doing what he does.

It was a rare public appearance for one of the least-known billionaires in the U.S. But the stakes were high. Arnold was testifying at a hearing of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

Commodity prices have been especially volatile in recent years -- skyrocketing and then crashing to earth -- and the federal regulator is considering dramatic rule changes to rein in speculators, whom many blame for the gyrating prices.

Arnold would tell you -- if he were inclined to tell you anything (and he rarely is) -- that he's a speculator. He might say, though, that that's not a bad thing to be. But call him what you want -- nobody has profited more when it comes to natural-gas trading in recent years.

His Houston-based hedge fund, Centaurus Energy, which manages more than $5 billion in assets, has never returned less than 50% in seven years of business.

Arnold's wealth reportedly constitutes a large chunk of the fund, which would make him the second-youngest self-made multibillionaire in the U.S. -- behind Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg (assuming you believe the social-networking company's theoretical valuation).

Arnold has the brain of an economist, the experience of a veteran gas man, and the iron stomach of a riverboat gambler. Perhaps most notable, though, is his uncanny ability to extract colossal profits from catastrophic circumstances.

He began his career as a wunderkind twentysomething trader at Enron -- and escaped that disaster not only with his reputation intact but also with the biggest bonus given to any employee, which he used to seed a new fund.

A few years later he earned $1 billion betting that natural-gas prices would go down just as a reputedly brilliant gas trader at Amaranth made a spectacularly disastrous bet in the opposite direction. More recently, as the commodities bubble burst in 2008, taking even more fund managers with it, Arnold foresaw the looming collapse and once again nearly doubled his money.

But now he faces the biggest test of his career. His mojo relies on his ability to make enormous bets. The CFTC, however, has vowed to impose trading limits that would target the industry's largest players. That, say observers, could be a dose of kryptonite for the supertrader.

As Arnold put it at the hearing, carefully reading from a prepared statement, "If allowed to take effect as currently structured, the new [position limits] will have a range of detrimental effects on the market." That qualified as a bold public statement by his standards.

But Arnold, who declined to comment for this article, is not fighting -- he's adapting. Besides wooing regulators in Washington, he has entered new corners of the business: buying natural-gas caverns, a prescient move that has made him a key middleman in the energy economy, and breaking into the next frontier in energy trading, liquefied natural gas.

"He's like a poker player who can see everyone else's cards," says a longtime trader who has known Arnold since his Enron days. But whether Arnold will emerge from the regulatory storm the same way he has from past squalls -- not only intact, but billions richer -- is less certain.

There are two kinds of natural-gas futures: the physical kind, in which investors enter a contract to buy or sell natural gas on a given day, and virtual ones, in which no gas trades hands. The latter are effectively side deals known as "swaps."

If a gas producer like Chesapeake Energy (CHK, Fortune 500) is worried that prices are going to fall below a certain level, for example, it can make a deal with a hedge fund like Centaurus that will pay an agreed amount if prices drop. But if they go up, Chesapeake has to pay out.

Centaurus, which started in 2002 with just a handful of traders and now has 70 employees, focuses on this virtual kind of trading. Still, Arnold, an intense worker with a wide network of contacts, aims to win by understanding the fundamentals of the gas market better than anyone else.

As Arnold told the CFTC (in one of the few statements he made that wasn't steeped in trading jargon), "I try to buy things whenever they're trading below what [our] analysis shows to be fair value and sell things whenever our analysis shows that the forward curve is higher than our analysis of fair value."

In his early days at Enron, Arnold made a name for himself by buying gas contracts in one region and selling them in another when their prices diverged because gas couldn't travel easily between states.

In 2000, however, Congress passed the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which allowed contracts tied to commodities to be exchanged in vast quantities, sparking a boom in electronic gas trading. (The law became known as the "Enron loophole," thanks to heavy lobbying by the then energy-trading giant.) Arnold's early trading experience, which gave him insight into the needs of gas customers all over the country, lent him an edge once virtual trading took off.

Arnold combines that knowledge with a willingness to make giant moves. Indeed, Centaurus earns the lion's share of its profits on a small number of enormous trades. "He only really puts on a trade of substance once or twice a year," says a person familiar with the fund. "But when he goes for it, he's so big he makes a fortune each time."

It's been a hugely rewarding strategy, but also a risky one. It means that Arnold himself may be just one missed wager away from his own blowup.

Arnold's ability to make megabets is helped by the fact that the fund has been closed to new investors since 2005. He has repaid nearly all his investors and now invests only his and his employees' capital, with none of the strings that come attached to other people's money.

"He and those lucky enough to be in his inner circle have a huge edge in that they can do whatever they want," says a commodities fund placement adviser.

Traders familiar with Arnold's style also credit a calm and disciplined manner that helps him stay eerily focused on the fundamentals of the market when other trades are creating distractions.

That was on display most notably during the Amaranth debacle. Amaranth, a $9 billion commodities hedge fund in Greenwich, Conn., was betting that natural-gas prices would rise in the winter, according to a Senate report that shed light on what happened in September 2006.

But as the season wore on, meteorologists began predicting a mild winter, and prices turned downward. Amaranth trading prodigy Brian Hunter started bleeding money, facing $3 billion in margin calls at one point.

As Hunter worked late on a Saturday in what would become a cataclysmic weekend for him, he e-mailed Arnold and tried to persuade him to buy Amaranth's positions before the market opened on Monday. Arnold wrote back the next morning, explaining that he hadn't been in the office for a couple of days, and coolly rebuffed Hunter.

The price was "still a long way from fundamental value," Arnold argued. In fact, he had separately been buying contracts that would pay off if prices tumbled even further -- and he was dead right. Arnold's timing was "remarkably accurate," according to the Senate report. Centaurus went on to 200% gains that fall, while Amaranth was forced to liquidate.

Centaurus's trading in those months netted nearly $1 billion. The result was a reported 317% return overall for Centaurus in 2006, a year when another natural-gas fund, MotherRock, also imploded trying to sustain a losing bet.

While others had panicked, Arnold had remained patient, waited until the right moment, and then opportunistically relieved others of their money. The best compliment may have come from a competitor who once described Arnold and his trading team to reporters as "like being on the Yankees, and he's Babe Ruth."

Commodities trading isn't the sort of profession that most children dream of going into. But by college, Arnold, who grew up in Dallas (his father, who died when Arnold was 17, was a lawyer), was showing an aptitude for numbers and complex calculations that can mark a great trader.

He attended Vanderbilt University, where professors remember him as an economics whiz, able not only to understand concepts instantly but also to do complex math in his head.

"We weren't shocked when he started making his billions," says professor Stephen Buckles. Arnold graduated in three years to work at Enron, which then was recruiting the four or five top econ majors from Vanderbilt each year. (His brother Matthew also worked at Enron.)

It was at the Houston energy company, under the tutelage of a stellar roster of traders, that Arnold really blossomed, becoming a well-paid star in the late 1990s. On Enron's natural-gas trading desk, which handled contracts totaling more than $1 billion a day, when he was only in his mid-twenties, Arnold alone reportedly earned Enron nearly $750 million in 2001. One colleague dubbed him the "king of natural gas."

After the accounting scandal brought down the company (the fraudulent schemes had little to do with Enron's legitimate trading business), UBS (UBS) bought the trading team and gave Arnold an $8 million bonus to stay. But he left, and eventually recruited former superiors like Greg Whalley, the last president of Enron, and trader Mike Maggi to reassemble a rump Enron team at Centaurus. He has also cherry-picked traders from other firms that have blown up.

Despite the scandal, natural-gas traders such as Arnold managed to retain their reputations, and the fund was able to launch fairly smoothly, aided by a wave of investor interest, first in hedge funds and then in commodities. Starting with smaller swaps, Arnold was able to rapidly build his firm.

One trade is typical -- the details of which come from a later court filing over a pricing dispute. In 2005, in the months leading up to hurricane season, Centaurus entered into "swing swaps" with producer BP (BP).

BP, which sells gas that travels through ports in Louisiana, was worried that prices might decline. Centaurus's meteorologists, however, apparently anticipated an intense hurricane season, which would probably drive up prices.

So Centaurus agreed to pay BP if prices slumped -- and vice versa if prices rose. When hurricanes Rita and Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast, gas skyrocketed, and Centaurus took home $3 million.

"They're gunslingers," says one lawyer who worked with BP at the time. "When you've got that much money, you can be everywhere at once, buying when others are selling, and always winning."

Halfway between Houston's downtown and uptown areas sits River Oaks, a historic neighborhood home to Houston's moneyed elite. Saudi princes and local notables like former commerce secretary and oil man Robert Mosbacher own houses there; it's said to be one of the wealthiest zip codes in the country.

Bayou Bend, an estate built by Houston's legendary Hogg family and now owned by the city's Museum of Fine Arts, is perhaps the most spectacular of all the homes. The preserved 1920s country estate is surrounded by lush, imaginative greenery. At the rear of the gardens, however, a jarringly angular modern edifice is under construction.

That's where John Arnold is going to live, in a 20,000-square-foot homage to cubism designed by New York architect Alexander Gorlin (Arnold also interviewed Robert A.M. Stern for the job). To build the home, Arnold had to tear down a creaky old estate called Dogwoods. That drew the ire of preservationists, who held a candlelight vigil in protest. Arnold won them over, arguing that by hiring a high-caliber architect, he would be creating a landmark, not a McMansion.

Like many a hedge fund manager, Arnold has strived to keep his life private. Unlike most managers, however, Arnold once worked at a company that was heavily investigated. The result: a trove of decade-old e-mails in the public record that offer glimpses of a typical twentysomething.

Arnold bought tickets to see the Dave Matthews Band and U2, and followed the Houston Astros and English Premiere League soccer. (He still plays soccer in a men's league every weekend.) He talked about getting drinks with his colleagues, and planned family vacations with his mother and brother.

Then and now, Arnold may have been one notch nerdier and more self-effacing than the average Enron trader. But he showed more than a touch of a trader's bravado. In one e-mail, he vowed to "squeeze all the fuckers" who he thought were wrongly betting on the direction of gas.

Today Arnold can afford a little swagger and a lot of the good life. He and his wife, Laura -- a Yale Law grad who once worked at the powerhouse law firm Wachtell Lipton and started an energy-exploration firm -- are modern-art collectors and have become known in philanthropic circles.

They have donated $700 million to a family foundation that gives money to charter schools run by an organization called the Kipp Academy, on whose board Arnold serves. Laura recently joined the board of Teach for America. "Once you get past a certain level of income," Arnold told friends at an alumni event at Vanderbilt, "it's all about the philanthropy."

Arnold's generosity, however, won't win him any friends among those who want to restrict commodities traders of all stripes. Observers say the CFTC is unlikely to budge on its vow to put position limits on market players. As a former Goldman Sachs executive, chairman Gary Gensler is market-friendly but strongly believes liquidity is best created by having many small traders, not several large ones.

Energy traders like Arnold counter that the big players help the market, both by providing liquidity when supply is threatened and by keeping prices in check with a willingness to short the market.

As the debate goes on, Arnold seems to be preparing for a future in which natural-gas trading is more limited. Centaurus has made investments in exploration and production companies; it has also hired liquefied natural gas traders in London.

Most significant, Arnold has become an energy market middleman by investing in valuable natural-gas storage facilities. A huge glut in supply, plus a dropoff in demand from mild seasons and reduced industrial need, has resulted in rock-bottom gas prices. So players are rushing to store gas in hopes of selling it when prices are higher.

In 2006 Arnold formed NGS Energy, which has carved a series of battleship-size storage caverns inside underground salt domes. "This is the opposite of a speculative play -- it's a bet on the future needs of the marketplace," says Laura Luce, a former Enron colleague of Arnold's who runs the venture.

Natural gas's storage and transportability as a fossil fuel, she says, also make it a key cog in the renewable-energy economy: "When there's no wind or sun, you fill in with the cleanest energy available, and that's gas. That's why gas storage is going to be a great business."

Of course, Luce is the one who makes the public pronouncement. Arnold, by contrast, is hardly in danger of becoming the sort of gas evangelist who appears in TV commercials, like his energy-trading colleague and fellow Texan T. Boone Pickens does for wind and natural gas. In trademark fashion, Arnold is staying behind the scenes and working on how to profit from the next disaster.

The Relentless Hunt for the Next Deal

PARIS, Sept. 29 — From his luxurious apartment on Avenue Foch in one of the choicest neighborhoods of Paris, Albert Frère tends his sprawling European financial empire with a slim cellphone pressed to his ear. A fellow business titan is calling to chat.

At 80, Mr. Frère is a little hard of hearing, a condition he attributes to weekend hunting trips, the shooting kind. But that does not deter him from prowling corporate Europe in a restless chase for a bargain — buying, selling and swapping pieces of some of the most prominent businesses in Germany, Italy, France and his native Belgium.

Deals, Mr. Frère freely acknowledges, while sitting in his favorite high-backed crimson chair in an apartment furnished with 18th-century antiques, are his drugs.

“Listen,” he said with a mischievous smile, “it’s so enriching and really amusing to succeed at a deal. It’s like when little children receive gifts. For me, it’s the same thing. It’s why I often say to work hard, but do it with pleasure.”

Mr. Frère’s heady, high-stakes play is just as intoxicating to analysts and rivals eager to anticipate the next move of this self-made billionaire, sometimes called the Warren Buffett of Belgium because of his diverse portfolio of value-driven investments.

For Europe, though, Mr. Frère has had a particularly parochial impact: he is a financier who has invested across national boundaries and thus helped build the kinds of cross-border conglomerates that reflect some of the founding principles of the European Union.

His investments outside Belgium span a range of industries, including banking, insurance, oil, energy and media, and his sales of those stakes to other foreign companies have nudged large companies to expand beyond their national markets. After buying a stake in Petrofina, a Belgian oil company, for instance, he later sold it to the French oil company, Total, which later merged with Petrofina in 1999.

For now, though, the most nagging question for Frère-watchers is what he will do with more than 4 billion euros ($5 billion) he reaped in July from selling his 25 percent stake in the German media company Bertelsmann.

After acquiring the stake in 2001, Mr. Frère had exhorted the German company to do an initial public stock offering. Ultimately, Bertelsmann bought back the stake to avoid taking the family-controlled company public. To finance the repurchase, Bertelsmann has had to sell some of its properties, including BMG Music Publishing.

Ordinarily, Mr. Frère — who makes his investments through his holding company, Groupe Bruxelles Lambert — is a discreet investor who shuns the limelight, saving his high-energy charisma to cultivate a blue-chip network of chief executives, fellow business tycoons and aristocrats.

But lately he has been more voluble, leading to speculation that he is poised for the Next Big Deal.

“I love discretion generally,” Mr. Frère said. His name, though, keeps surfacing in business headlines for his eclectic interests but basic approach: “We study investment proposals for every angle of profitability. We try to be objective, impartial. There is no place for passion.”

His deals include selling Banque Bruxelles Lambert to the Dutch financial giant ING; a stake in Royal Belge insurance to the French insurer Axa; and a stake in RTL, the Luxembourg-based television broadcaster, to Bertelsmann. Last year, Groupe Bruxelles Lambert played an important role in the decision by the French utility Suez to buy the remaining shares it did not already own in Electrabel, the biggest Belgian electric utility.

As the largest individual shareholder in Suez, he is a behind-the-scenes player in the continuing efforts to merge it with Gaz de France, the country’s top gas supplier, which would create Europe’s largest utility, with market capitalization of 75 billion euros ($95 billion).

Mr. Frère has also rapidly amassed the largest single stake in Lafarge, a French cement maker, and may raise that beyond 11 percent, to put more pressure on the company to deliver results. Through Compagnie Nationale à Portefeuille, another holding company, he recently paid 120 million euros to Suez for a 5 percent stake in the French television channel M6.

Now, Mr. Frère and his close friend Bernard Arnault, chairman of LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, the French luxury-goods company, are poised to create a joint venture, according to a person close to both men who spoke on condition of anonymity. The person would not disclose more details until a formal announcement of the deal, which was expected to be soon.

But the market is still waiting for something more dramatic from Mr. Frère, who has become something of an elder statesmen in the European business community.

“He sold Bertelsmann much sooner than everybody expected,” said Tom Simonts, a KBC Securities analyst in Belgium. “Why do that?”

It has been a long road for Mr. Frère, a high school dropout and son of a nail merchant. His widowed mother took over the family scrap-iron business at age 40, while raising three children.

From his mother, Mr. Frère recalled, he acquired an enduring thriftiness, a habit he demonstrates every time he switches off blazing lights.

“ ‘Extinguish the lamps,’ ” he recalled his mother saying. “ ‘We don’t have the resources of the Rothschilds!’ ”

Born and raised in the southern Rust Belt of Belgium, Mr. Frère left school at age 18, without regrets.

“A diploma is important at the beginning,” he said, “but for the rest of a professional career, the tools of success are constant work, business instincts, pragmatism and charisma.”

In the 1950’s, he parlayed money from the family nail-making business to buy a handful of steel makers. It was the beginning of a career based on an uncanny sense of timing.

He was one of the first industrialists to realize that the Korean War would spur demand for steel. He then made a fortune in 1979 when the Belgian government nationalized the country’s steel companies before the industry slid into decline.

Mr. Frère forged what became a lifetime alliance with Paul Desmarais, a Canadian entrepreneur, and with the money from the state takeovers they bought Groupe Bruxelles Lambert in 1982, leading to a cascade of investments.

With Mr. Desmarais acting as the strategist and Mr. Frère executing the deals, they bought and sold many of the crown jewels of the Belgian business world, which had gained in value as the European Union evolved into a single market.

There was grumbling in Belgium that he was selling out his country. But Mr. Frère had already become part of the aristocracy, having been awarded the title of baron by King Albert II in 1994. Mr. Frère also has been awarded the French Legion of Honor.

Today, Mr. Frère is one of Europe’s richest men, with a net worth estimated by Forbes magazine at more than $3 billion. A collector of fine art who owns paintings by Renoir and Magritte, Mr. Frère divides his time largely between Brussels, Paris and a home in Gerpinnes, in the Belgian countryside.

Alain Minc, an economic adviser and longtime friend of Mr. Frère’s, has watched him navigate the Continent’s boardrooms. He has also seen him in tough negotiations; together they brokered a truce between two of the richest men in France— François Pinault, chairman of the PPR retailing empire, and Mr. Arnault — in a feud over the Italian fashion house Gucci.

“He’s not a mere investor,” Mr. Minc said. “He participates in the game because he enjoys human relations and he enjoys being friends. And he has a very skillful ability for networking by creating empathy. He enjoys life. He enjoys food and wine and laughter, and so people like him.”

To hammer out the deal with Bertelsmann for the sale of Groupe Bruxelles Lambert’s 25 percent stake in the company, Mr. Frère organized a dinner at his home in Belgium this year with his wife, Christine; his son, Gérald, 55, who is chairman of the board of Compagnie Nationale à Portefeuille; the chief executive of Bertelsmann, Gunther Thielen; and Liz Mohn, doyenne of the family that is the largest shareholder in Bertelsmann.

Thomas Middelhoff, a former chief executive of Bertelsmann and a board member of The New York Times Company, negotiated the sale of the stake to Mr. Frère in 2001 in exchange for a controlling interest in Mr. Frère’s pan-European broadcaster, RTL. He said he tried to strike the best deal by imagining Mr. Frère’s next move and countering his most lethal weapon.

“I tried to beat him with the same charm — tough and clear, with a firm position,” Mr. Middelhoff said, noting that their business relationship evolved into friendship.

But Mr. Frère’s moves often remain so cryptic to the market that analysts and rivals are forced to glean clues from his rare public utterances.

He offers few clues about how he will spend the proceeds from the Bertelsmann sale. “There are numerous opportunities in many sectors, including investments in quasi-industry or private equity,” he said, noting that whether the industry is media or cement, the goal is the same: “a search for value.”

Succession, he said, is assured with a talented and loyal group of managers and his son, Gérald, waiting in the wings. His younger son, Charles-Albert, died in a car accident in 1999. Friends say he will pursue the next deal until his very last day, and he has clearly negotiated his terms. “I have,” he said, “simply erased the word retirement from my vocabulary.”

Checkmate for a Wall Street wizard?

When Lehman, AIG, and Merrill Lynch were in crisis a year ago, Chris Flowers could be found at the scene. He survived the maelstrom - but now he has his own billion-dollar problems to worry about.

(Fortune Magazine) -- The week of Sept. 7, 2008, started out innocently enough for J. Christopher Flowers. The billionaire, whose eponymous private equity firm invests mostly in troubled financial companies, was in Tokyo to attend a board meeting when he received a call from a senior executive at Bank of America. The executive wanted him to return to New York as quickly as possible to partner in a potential deal to buy Lehman Brothers, which was in increasingly desperate straits.

Flowers flew immediately to New York. By seven on Thursday morning he was studying Lehman's books in a Midtown conference room. Still there 14 hours later, Flowers got a call from an executive at AIG inviting him to lunch the next day with Bob Willumstad, the insurance giant's then CEO. At lunch Willumstad showed Flowers a piece of paper revealing that AIG's cash balance would be a negative $6 billion within days and a negative $25 billion a week after that. Flowers began plotting ways to avert a collapse, but despite trying to enlist Warren Buffett and others, he couldn't put together an acceptable proposal. He was, however, the one who pulled aside then-Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson -- the two had worked together at Goldman Sachs -- and alerted him to AIG's looming crisis.

Before the weekend was out Flowers found himself immersed in yet another deal, one that may prove to be the most controversial financial merger of recent years. On Saturday morning, while top Wall Street executives convened at the New York Federal Reserve Bank to try to save Lehman, Flowers met with Bank of America's executives, who dropped another bombshell. BofA was no longer kicking Lehman's tires. "We want to buy Merrill Lynch this weekend, and we need your help on that," they told him. Flowers, who occasionally moonlights as an investment banker (especially for old clients such as BofA), signed on.

During the week last September when it seemed as if the world's financial system was imploding, Flowers, 51, found himself at the epicenter of the frenzy. Whether it was at Lehman, AIG (AIG, Fortune 500), or Merrill Lynch, he was nearly as omnipresent as Hank Paulson. Flowers describes his days of shuttling from crisis to crisis as "like being at D-Day."

That was hardly the first time Flowers had turned up at the sickbed of a giant financial entity. He has an uncanny knack for popping up in the midst of calamities. The student loan company Sallie Mae and Bear Stearns are just two of the other ailing operations he has bid on -- but not acquired -- in the past 18 months. Indeed, that may be Flowers' most striking trait as a dealmaker: He has the unlikely distinction of being most famous for the deals he hasn't done.

Of late, however, it's the ones he did do that have been dogging him. Flowers is struggling to salvage a series of ill-timed investments that he made just before the financial crisis got really ugly and dragged already distressed institutions down further than he thought possible. His billion-dollar stakes in Japan's Shinsei Bank and in Hypo Real Estate and HSH Nordbank, both in Germany, have crumbled.

Flowers' $7 billion second fund is down between 60% and 70%, according to estimates from knowledgeable sources. (Flowers declines to say.) And some of his biggest bets, such as Hypo and HSH, are unlikely ever to make his investors whole.

To be sure, Flowers can take consolation in a reported $1.5 billion net worth. Still, it has to be humiliating for a renowned brainiac accustomed to one success after another at the highest levels wherever he has competed: chess, Harvard, and Goldman Sachs (GS, Fortune 500), where he was once the firm's youngest partner at age 31. After all, he personally pocketed about $1 billion on his first big deal as a private equity investor -- Shinsei Bank, ironically -- only to see that triumph evaporate, along with his investors' money, as the bank's fortunes turned.

As sterling as his r�sum� is, one question is inescapable: Is Flowers a one-hit wonder as a private equity investor? Or is he just suffering a miserable year in the midst of one of the most disastrous periods ever for the sorts of investment he specializes in? "I did not foresee the cataclysm that was going to happen," Flowers says of last year's meltdown. Fair enough -- many didn't. But it's far from clear that he'll be able to mount a comeback.

Before the descent, it always seems, comes hubris. It would be hard to find a clearer example than Chris Flowers, a man who seems reserved to the point of timidity, but who on a few occasions has issued the sort of brash proclamation that you'd associate with the likes of Donald Trump. Behold Flowers, for example, in June 2008 telling investors in his $7 billion fund that "every single investment will make money." Every single investment! Bear Stearns had collapsed a few months before, and asset prices of financial institutions seemed to be at their nadir. Flowers pronounced it the "Super Bowl of investment," adding, "It's no time to be sitting in the bleachers."

Then, in February of this year, Flowers told a Manhattan conference titled "The Big Fix" that "lowlife grave dancers like me" will make a "tremendous fortune" from the detritus of the collapse of numerous financial institutions. He asserted that "governments everywhere -- this government and around the world -- are going to own a lot of stuff, and they are going to be not very adroit, not very commercial."

Sheila Bair, chairman of the FDIC, was miffed by Flowers' braggadocio. And another of Flowers' moves may only irk her more. Flowers personally bought a tiny bank in Missouri last year, sight unseen. The sole purpose, some believe, was to circumvent rules that the regulator has been considering for how private equity firms will be permitted to invest in failed banks. So today Flowers is chairman of the former First National Bank of Cainesville, with $17 million in assets, which he not so humbly renamed Flowers National Bank. ("Grow with us" is the new slogan.) "He bought that bank for just one reason: If you have a bank charter, you can apply to get on the FDIC failed-bank distribution list," says someone who knows him.

Given the FDIC's current power in selling off bankrupt banks, alienating its chairman is not a wise move. "He's a pariah in D.C.," says one private equity investor. (Through a spokesman, Bair declined to be interviewed.)

Flowers knows he has rankled the FDIC. And while contrition is not an emotion he wears well, he is feeling it. He says he has opened a diplomatic front with Bair and is trying to make amends. "It is in our interest to have low-key, smooth relationships with government and regulators," he says. "Our aim is to be understated and low key and noncontroversial."

By all appearances, he is fully implementing that policy. With a newly hired PR representative seated next to him in his office on Manhattan's Fifth Avenue, he shies away from all but the blandest observations. Indeed, meeting Flowers in person, it's hard to imagine him in Trump mode. His horn-rimmed glasses give him an owlish look, and his distracted intellectualism suggests an academic rather than a corporate buccaneer.

Flowers has the patrician pedigree of the old-school Wall Street banker; he's the antithesis of the back-slapping fraternity-brother type. Sure, he enjoys outdoor activities: He likes to sail near his vacation home in North Haven, Maine, and he recently returned from a sailing trip off the coast of Croatia. But it seems no accident that he prefers chess -- a contemplative, intense mind teaser of a pastime -- to the social staples of banking, golf and tennis. As he puts it, "There is no man in America less interested in sports than me." When he first started at Goldman Sachs, he recalls, he was nervous that his lack of sports knowledge would make him an outsider at the firm.

Flowers may appear nerdy, but he has a quirky charm. And his low-wattage exterior belies a steely determination, whether at the chessboard or in the ongoing battles among Wall Street alpha males, that has served him well. He may not be outgoing, but he's the sort of person a top executive can feel comfortable trusting. "I like someone who is 24/7, always reachable, keeps their cool, thinks through problems carefully and as a partner," says James B. Lee Jr., a vice chairman at J.P. Morgan Chase who has worked with Flowers in myriad capacities and whose company is a limited partner in his funds. "He's a very, very good and natural partner."

Flowers wasn't present at the Sept. 15, 2008, press conference announcing BofA's acquisition of Merrill Lynch. But his name was invoked repeatedly, and today he probably wishes it had never been uttered. BofA CEO Ken Lewis cited Flowers' conclusion that Merrill had "a much lower risk profile" than it had the year before. Flowers, he continued, "was very complimentary" of the actions taken by Merrill CEO John Thain to strengthen the company's finances.

Initially hailed as brilliant, the BofA/Merrill merger has come to be viewed as a disaster, with revelations continuing to emerge about everything from the toxic surprises lurking among Merrill's assets to hefty bonuses for some Merrill employees to the extraordinary pressure Paulson and Ben Bernanke, the Fed chairman, put on Lewis to complete the transaction. Flowers suffered the indignity of having his work dissected in a congressional hearing, with Rep. Dennis Kucinich (D-Ohio) questioning whether "Ken Lewis's management team failed to do due diligence," and Paulson acknowledging he was aware of such criticism.

The more fundamental question, for those outside Washington, is, Why did BofA agree to such a high price for a company on the verge of bankruptcy? Flowers didn't negotiate the terms, but he played a major role: As the key adviser, he endorsed the bank's decision to pay a 70% premium for Merrill's shares. And he issued a "fairness opinion," certifying that the price Bank of America (BAC, Fortune 500) was paying was justified. (For that work, which took a single weekend, Flowers was paid $10 million, with another $10 million going to Fox-Pitt-Kelton, a small investment bank in which he owns a stake.)

For his part, Flowers says Lewis never asked him to update his original fairness opinion to reflect changes in Merrill's circumstances, and never consulted him again about the deal after that weekend. He says he and his team valued the Merrill assets as well as they could with the information available. Although Flowers had only a weekend to comb through Merrill's financials, he was actually steeped in them: He had reviewed the books nine months earlier when Merrill was raising capital and Flowers (this time as a private equity fund manager) was considering an investment. Flowers passed then -- the price was too high, he says -- but kept tabs on Merrill and noted that through the course of 2008, the firm raised billions in capital, sold a $30.6 billion chunk of troubled assets to Lone Star Funds for 22� on the dollar, and sold its stake in Bloomberg LP for around $4.5 billion. But those moves, it would later become clear, were not enough.

The fiasco has been a black eye for Flowers, who takes pride in maintaining the prestige of his old role as a mergers-and-acquisitions adviser even as he focuses on investing for his private equity fund. Flowers defends his reasoning. He asserts that Lewis coveted BofA and that, since it was an all-stock transaction and BofA's share price has fallen, the cost was dramatically lower than if BofA had paid cash. In sum, he says, "I thought it was a reasonable price."

How Flowers, the scion of a once-wealthy timber, banking, and baking family with roots in Alabama, became the Zelig of finance is a story of drive, intelligence, and a little serendipitous timing. Born in California, Flowers moved to Weston, Mass., a suburb of Boston, at age 6, when his father retired from the Navy and took a job as an administrator at Harvard Business School. His mother grew up in Queens, N.Y., and dropped out of Barnard College to get married. She was 18; her fianc� was 30. She eventually got a master's degree and became a children's librarian (and a leader in the field).

In high school Flowers was a math whiz and a chess champion. He showed at least hints of a mordant sense of humor, choosing as his yearbook tag line the quotation "The horror, the horror" from Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness" (this was several years before the movie "Apocalypse Now" propelled the phrase into the pop culture lexicon). Flowers went off to Harvard, where he majored in applied mathematics. There, he says, "I found people at Harvard who made me look like a moron at math." Flowers knew he wanted to go into business. His father, who died when Flowers was 21, had told him, "If there is one thing you should do," it is to go to Harvard Business School.

He didn't follow his father's advice. Instead Flowers got a summer job at Goldman Sachs after his sophomore year, courtesy of a Harvard classmate whose father was the prominent Goldman partner Arthur Altschul. After graduating from Harvard a semester early, Flowers joined Goldman full-time in March 1979, working as an analyst for partner Steve Friedman in M&A. "The first thing I learned at Goldman was how to work hard," he says. That first year he worked "365 days straight," and Goldman paid him $16,000. He says he also learned how to "sell," the mundane but crucial aspect of investment banking that requires bankers to persuade clients to hire you and your firm rather than someone else and his firm.

Flowers bloomed at Goldman. The firm asked him to forgo business school and become an associate but didn't increase his pay. "I remember being irritated," he says. He was invited into Goldman's nascent financial institutions group as the M&A guy and quickly shone. By 1988 he'd been named a partner at the tender age of 31, the youngest at the time to attain that distinction.

Flowers was extraordinarily successful at Goldman. He thrived as he worked on many marquee transactions in financial services, including the NationsBank/Bank of America merger and Norwest's takeover of Wells Fargo.

But his tenure at Goldman ended with a thud in 1998. His mentor, then-chairman Jon Corzine, had been pushing the idea of an initial public offering. Flowers was a key architect of the technical aspects of the proposed IPO. Goldman's partnership voted in favor of the idea. But in the wake of the collapse that fall of Long-Term Capital Management and increasingly shaky market conditions, the management committee chose to shelve the IPO. Flowers decided to leave Goldman that November. Two months later four of the six members of the management committee, including Paulson and John Thain, voted to oust Corzine.

Flowers was "an ambitious guy, not in a bad way, who wanted to move up in the firm," says former Goldman vice chairman Robert Steel, who was one of Paulson's deputies at both Goldman and the Treasury. As Steel sees it, Flowers made one "big bad bet" on Corzine, and once Corzine lost the IPO battle, "Chris ran out of runway at the firm."

Flowers concedes the point. "The politics of it had been very bitter and divisive and ugly," he says. He quickly came to the conclusion that "the future was not bright for me there" and decided to take his growing fortune and move on. He and Corzine, now governor of New Jersey, remain close; Flowers manages some of Corzine's considerable fortune. (Corzine did not respond to requests for comment.) Flowers takes solace in the fact that Goldman soon reversed its decision and approved an IPO, which, among other things, left Flowers with hundreds of millions of dollars of Goldman stock.

By the time he left Goldman, Flowers had already decided to use his M&A expertise and knowledge of the financial industry to become a private equity investor. Almost immediately he began putting tremendous energy into figuring out how to buy a Japanese bank. Flowers says his experience in the savings-and-loan crisis of the 1980s convinced him that buying banks when they were down and out could be extremely lucrative. And after Japan's so-called lost decade, the country was stocked with numerous "zombie banks" ripe for turnarounds.

A mutual friend introduced Flowers to Tim Collins, a former Lazard banker who had formed a private equity firm, Ripplewood Holdings, and also happened to be intrigued by Japanese banks. Collins gave Flowers office space at his firm, and eventually they set their sights on Japan's ailing Long Term Credit Bank (LTC). Flowers scrubbed the books and in a computer spreadsheet projected the potential for 70% annualized rates of return. He has framed his handwritten analysis from March 1999 as a reminder of the light-bulb moment. He knew he was onto something.

But the obstacles were daunting. For starters, there was a diplomatic challenge: The Japanese government had never permitted Americans, let alone private equity investors, to buy a bank. Then there was the financial one: how to acquire LTC without drowning in its sea of bad loans.

Collins and Flowers turned out to be perfect partners. The two couldn't be more different -- Flowers is ascetic; Collins, colorful -- but each played his part. The two assembled a cadre of financiers including powerhouses like GE Capital (GE,Fortune 500) and Citigroup (C, Fortune 500), while bringing in players with diplomatic credibility, such as the chairman of Mitsubishi, Masamoto Yashiro; David Rockefeller; and former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker. Collins then deployed his team in the sensitive negotiations with Japanese officials. Meanwhile Flowers focused on the minutiae of the deal's complex structure and devised a mechanism that ensured the bank's bad loans would stay with the Japanese government.

Ultimately Collins and Flowers persuaded the Japanese government to sell the bank to their consortium of 12 major investors for $1.1 billion in March 2000. "Getting the deal done was a great collaboration," Collins says, "and without any one of [our partners], it probably wouldn't have happened." When the deal was announced, Collins and Flowers were invited to visit the Japanese Prime Minister at the Diet, the Japanese parliament.

In February 2004, after years of hard work fixing the bank, renamed Shinsei -- "rebirth" in Japanese -- the investors launched an IPO. So lucrative was it that David Rubenstein, co-founder of competitor Carlyle Group, dubbed it the "most successful" private equity deal in history. On the first day of trading the stock jumped 58%, valuing the bank at almost $10 billion, a return at that moment of nearly 10 times the original $1.1 billion investment. It is generally accepted that Collins and Flowers each made around $1 billion, though neither will discuss his payday.

Collins, who extracted all his money over time, had to share his fortune with a few investors, plus pay the overhead for Ripplewood (which has most recently been in the news because its entire $275 million investment in Reader's Digest was wiped out in that company's bankruptcy filing).

Flowers, who took out only about one-third of his profit at the time of the Shinsei IPO, did not have to share his haul with anyone, since he had no fund at that time. The two partners ended up parting ways over the bank's strategic direction but remain friendly, despite reports of a tiff. (Flowers is planning to visit Collins at his Adirondacks "camp.") In his first big deal as a private equity investor, Flowers had reached the pinnacle. But he would soon find defeat in the very company that had provided his triumph.

The extraordinary success of the Shinsei IPO transformed Flowers into a rock star in the private equity world. He quickly raised $900 million for a debut fund in 2002, and then $7 billion for a second fund in 2006, the most money ever raised to invest solely in the financial services sector.

Flowers didn't look far for investments. Not only did he keep most of his initial investment in Shinsei, but he also used his investors' cash to buy more stock before the IPO, more soon after the IPO, and still more in November 2007. When all was said and done, Flowers and his investors had sunk $2.5 billion into Shinsei. But even as he did that, the bank was pouring billions into asset-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations. The losses mounted, and Flowers watched as Shinsei shares tumbled.

Today that holding, which represents about 33% of the company, is worth around $1 billion. Flowers says he does not regret keeping -- and then adding to -- his position in the Japanese bank. "I believe that Shinsei has a very good long-term future, and I expect that we will see that emerge over time," he says. Flowers just brought back the bank's former CEO and orchestrated a merger with Aozora, a Japanese bank controlled by Cerberus, the U.S. private equity firm. And perhaps there are already some hopeful signs: On July 31, Shinsei reported its first quarterly profit in a year -- $55 million.

Flowers is reluctant to be specific about his funds' other holdings. He has investments in eight banks across the globe: Hypo Real Estate and HSH Nordbank in Germany; IndyMac and Flowers National in the U.S.; Shinsei in Japan; NIBC in the Netherlands; OJSC Investtradebank in Russia; and NBFC Sicom in India. He also owns the stake in Fox-Pitt-Kelton (which Macquarie Group is reported to be bidding for) and pieces of other small institutions.

The IndyMac transaction is revealing in its own way. Flowers is part of a group of private equity firms that agreed to buy the failed savings and loan -- now OneWest of California -- from the FDIC last fall (before Flowers made his comments about being a "grave dancer"). But Flowers was so sensitive to the dismal results he has been generating that he offered some of his investors a special arrangement: They could invest directly in IndyMac rather than through Flowers' fund. That means those investors won't have to pay management or success fees on that investment. When a fund manager voluntarily eschews his 2 and 20, you know he has some angry customers.

The list of deals that Flowers explored but didn't complete is long. There's Lehman; AIG; Bear Stearns; Refco, the scandal-tarred commodities trader (now part of MF Global (MF)); Northern Rock, the troubled British bank; and Friends Provident, the British insurer.

Most infamous, though, was his proposed $25 billion takeover of Sallie Mae, the student-loan provider, in April 2007. The Sallie Mae deal was to be Flowers' largest and most audacious. But when the market began to crack that summer, Flowers and his consortium, including J.P. Morgan Chase (JPM, Fortune 500) and BofA, invoked the "material adverse effect" escape hatch in their agreement (they cited legislation that would change the rules on student loans) and then tried to bail out of the $60-per-share deal. Flowers then made a new offer at $50, only to be rebuffed by Sallie's board. Acrimony, lawsuits, and bad press followed.

Flowers looked to be on the hook for the bulk of a $900 million breakup fee until the parties settled, with J.P. Morgan and BofA agreeing to lead a group of banks in refinancing a $31 billion credit line for Sallie Mae. Flowers emerged with a tarnished reputation -- but at least his investors were spared disaster. The shares, which he once agreed to buy at $60, now trade at around $10.

Flowers' worst mistake came in a deal he did close, just before his June 2008 comment about the moment being the "Super Bowl of investment" opportunities. In May his fund (along with Shinsei) led a $1.5 billion tender offer to acquire 24.9% of Hypo Real Estate Holding, a Munich-based commercial real estate lender. The Hypo shares were faltering, having fallen close to two-thirds in the months before Flowers' tender offer. But Flowers still paid a 25% premium. Even stranger, Flowers bought the shares in the market rather than directly from the company, which was short of capital. This seemed like a monumental miscalculation. "That was what the company wanted," Flowers says. "At that time they felt they didn't need capital. And they were wrong, and we were wrong."

That's an understatement. After Lehman failed and financing markets seized up, Hypo's Depfa Bank subsidiary, based in Dublin, could no longer obtain short-term loans. Hypo sought assistance from Germany's bank-rescue fund a mere four months after Flowers made his investment, incurring political wrath in the process. The German government ended up owning 90% of Hypo, drastically diluting Flowers' stake. In a year he has lost about 87% of his $1.5 billion investment. Hypo "has been the most difficult experience we've had, and is a big loss and was a mistake," he says.

His other German investment is a 27% stake in HSH Nordbank, bought nearly three years ago for $1.8 billion. After a $4.5 billion government rescue in May, Flowers' position has been watered down to 10.7% and is no longer publicly traded. He did own an insurance company in Germany, Wuba, which he sold to AIG in August 2007 for an undisclosed amount of cash. "We did very well on that," he says, though he declines to provide specifics.

Even in his private life, it seems, Flowers couldn't avoid buying at the top of the market. In 2006 he paid $53 million -- still the record price for an individual property in New York City -- to buy the Harkness mansion, a century-old, oversize limestone townhouse on East 75th Street. He then reportedly spent another $15 million or so gutting and renovating it. Earlier this year he quietly put it up for sale at a discount -- a steal at $49.95 million -- because he and his wife are splitting up. So far there's no sign of takers.

Like more than one founder, Flowers is synonymous with his 40-person firm, which is officially known as J.C. Flowers & Co. But Flowers still loves to get personally immersed in deals -- he's anything but a delegator. He enjoys a detailed dive into the numbers. "I have found that to be one of the single most useful things you can do," he says.

It's precisely this notion that Flowers is a solo chess player rather than a team quarterback that his critics -- who hide behind the cover of anonymity -- cite as an explanation for his recent failures. "The firm revolves around him," explains one banker. "He never built a team. There is no real process, no real investment committee. There's just Chris." Flowers rejects this characterization, not surprisingly, and he insists he has an able team of senior bankers who are deeply involved in his projects.

Despite Flowers' slumping investments, he remains a powerful force in his investing niche. And he has a legion of impressive fans. Says Gary Parr, a Lazard banker who is both a onetime competitor and Flowers' partner in the successful Fox-Pitt investment: "I trust him as much as anybody I know, and that's worth a lot, to know that you can trust somebody to do what they say they will do, or to say I'm not going to do it and walk away with clarity."

Nobody doubts Flowers' brainpower. No less a judge than Warren Buffett tells Fortune, "I think he's a smart guy." (Buffett spoke with Flowers during the attempt to rescue AIG.) But is intellectual firepower enough? "He did one great assisted transaction in Japan," observes another banker, "and off that he raised $7 billion. The great failing in private equity is to assume that you can repeat the past. I think he just assumed, for instance, he could repeat Shinsei over in Germany. Big mistake."

Flowers is facing increasing resistance from investors. Last year he set out to raise $7 billion for his third fund but attracted only $2.5 billion. And some of his investors are trying to defect. They have been shopping their stakes to raise cash. But it has been rough finding buyers at anything resembling an attractive price, a clear sign that the market is not confident Flowers will be able to salvage much value in the second and third funds. Says one investor who buys and sells limited-partner positions: "In portfolios we have looked at, we have assigned zero value to [investments in Flowers' second and third funds]."

Fortunately, Flowers has plenty of cash to deploy. His third fund still has around $2 billion, plus a potential $3.6 billion from Chinese Investment Corp. and others. There remains a near flood of investment opportunities in a financial sector still desperate for equity. "The number of companies that need capital is unusually large," he says.

Flowers ventures optimism about Shinsei but otherwise restrains himself when it comes to talking about the future of his other holdings or what he might invest in. As you might imagine, he's not making any new predictions these days.

China's amazing new bullet train

This year Beijing will spend $50 billion on what will soon be the world's biggest high-speed train system. Here's how it works.

When lunch break comes at the construction site between Shanghai and Suzhou in eastern China, Xi Tong-li and his fellow laborers bolt for some nearby trees and the merciful slivers of shade they provide. It's 95 degrees and humid -- a typically oppressive summer day in southeastern China -- but it's not just mad dogs and Englishmen who go out in the midday sun.

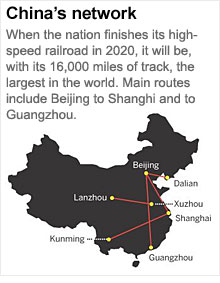

Xi is among a vast army of workers in China -- according to Beijing's Railroad Ministry, 110,000 were laboring on a single line, the Beijing-Shanghai route, at the beginning of 2009 -- who are building one of the largest infrastructure projects in history: a nationwide high-speed passenger rail network that, once completed, will be the largest, fastest, and most technologically sophisticated in the world.

Creating a rail system in a country of 1.3 billion people guarantees that the scale will be gargantuan. Almost 16,000 miles of new track will have been laid when the build-out is done in 2020. China will consume about 117 million tons of concrete just to construct the buttresses on which the tracks will be carried. The total amount of rolled steel on the Beijing-to-Shanghai line alone would be enough to construct 120 copies of the "Bird's Nest" -- the iconic Olympic stadium in Beijing. The top speed on trains that will run from Beijing to Shanghai will approach 220 miles an hour. Last year passengers in China made 1.4 billion rail journeys, and Chinese railroad officials expect that in a nation whose major cities are already choked with traffic, the figure could easily double over the next decade.

Construction on the vast multibillion-dollar project commenced in 2005 and will run through 2020. This year China will invest $50 billion in its new high-speed passenger rail system, more than double the amount spent in 2008. By the time the project is completed, Beijing will have pumped $300 billion into it. This effort is of more than passing historical interest. It can be seen properly as part and parcel of China's economic rise as a developing nation modernizing at warp speed, catching up with the rich world and in some instances -- like high-speed rail -- leapfrogging it entirely.

But this project symbolizes even more than that. This monumental infrastructure build-out has become the centerpiece of China's effort to navigate the global financial crisis and the ensuing recession.

Last November, as the developed world imploded -- taking China's massive export growth and the jobs it had created with it -- Beijing announced a two-year, $585 billion stimulus package -- about 13% of 2008 GDP.

Infrastructure spending was at its core. Beijing would pour even more money into bridges, ports, and railways in the hope that it could stimulate growth and -- critically -- absorb the excess labor that exporters, particularly in the Pearl River Delta, were shedding as their foreign sales shrank more than 20%.

A single province, Guangdong, was thought at the end of 2008 to have more than 20 million unemployed workers, many of whom appeared intent on heading back home to poorer, rural provinces with nothing much to do. Little focuses minds in Beijing more than the prospect of huge numbers of idle young men. It conjures up images of social instability that could conceivably strip the Communist Party of its primary source of legitimacy: economic growth and the improving living standards it has been providing for nearly 30 years. Beijing, in other words, had a lot riding on the bet that a massive boost to infrastructure spending could ameliorate the downturn.

Just over half a year later, the medicine appears to be working (at least so far). Railway worker Xi Tong-li, in fact, is one small example of that. Last fall he was toiling in a factory that made industrial fasteners for export in the city of Dongguan in Guangdong province -- a factory that is now closed. When Xi, a native of rural Henan province, lost his job, he called a friend who was working on a spur of the high-speed rail line that will eventually connect Beijing with Shanghai, cutting travel time from around 10 hours today to about four when the line opens in a couple of years. Two months later he was hired at a wage of $250 per month. "I'm happy to have a job so that I can still send money back [to Henan] and help my parents," he says.

It's unclear just how many of those laborers who lost their jobs in the export sector have been absorbed by China's accelerating infrastructure build-out -- the biggest portion of which by far is construction of the high-speed rail network. Unemployment -- estimates range from 10% to 20% -- remains the government's primary economic concern.

As David Li, an economist at Beijing's Tsinghua University, says, there's no doubt that "the acceleration of [the massive railroad build-out] is playing a key role in China's recovery." In mid-July, Beijing announced that second-quarter growth came in at 7.9%, and that the quarter-on-quarter upswing was the fastest the nation had seen since 2003. Economists at Goldman Sachs now believe China will expand at 8.3% this year -- exceeding the 8.1% goal set by Beijing in January, and dismissed then as unrealistic by most private economists.

That the government-led infrastructure spending, as Li says, is driving this growth is beyond dispute. A recent survey by Australia's mining industry shows that China's overall steel production capacity has actually increased by 10% to 12% over a year ago, despite the worst global downturn in decades. But nearly all that production is being used domestically, the survey said.

And across the Chinese landscape, it's pretty easy to see why. Whether in Dalian in the northeast, Wuhan in the west, or Shanghai in the east, one constant is the sight of massive concrete buttresses about 246 feet apart, lined up one after another in rows extending as far as the eye can see. The buttresses support the tracks over which the high-speed trains will run. They weigh 800 tons each and are reinforced by steel cables. There are close to 200,000 of them being built, all across the country.

At a moment when the developed world -- the U.S., Europe, and Japan -- is still stuck in the deepest recession since the early 1980s, China's rebound is startling. And the news comes just as Washington is embroiled in its own debate about whether the U.S. requires -- and can afford -- another round of stimulus, since the first one, earlier this year, has thus far done little to halt the downturn. Tax cuts made up about one-third of the $787 billion package, and only $60 billion of the remaining $500 billion has been spent so far.

Proponents of more stimulus are likely to cite China's example of what a properly designed stimulus program can accomplish. Maybe so. But a closer look at China's high-speed rail program also reveals some risks that should factor into the "Why can't we do that?" debate that's surely coming in Washington.

Xia Guobin, an amiable 51-year-old, is vice president and chief engineer for China Railway Construction Co., the largest of three state-owned companies that are the primary contractors for China's railway build-out. Sitting in the company's Beijing headquarters, I tell him it's likely that U.S. policymakers will look at China and suffer a pronounced case of infrastructure envy. He chuckles and says, "Well, it's not as if we were all standing around here doing nothing when the world financial crisis hit."

He says it jokingly, but it's the first key to understanding why China seems to be getting quick economic traction from its spending. As anyone who lives here knows, the government's massive infrastructure investment has been underway for years. Ports, bridges, airports, highways -- China in three years' time will have more miles of multilane highways than exist in the U.S. The rail program itself began four years ago, and the first spur opened just before the Olympics last year, linking Beijing with the city of Tianjin, 70 miles away -- a ride that now takes just about 30 minutes.

This is the definition, in other words, of "shovel-ready." China, for instance, was able to more than double its rail spending this year because, for the most part, it could simply move up plans that were already in place. That means existing orders for steel and cement and process-control systems and computer chips were all expanded (and given the softness in the export sector, most suppliers have had no trouble meeting the increased demand).

Last year China Railway Construction Co., the nation's largest railroad builder, hired 14,000 new university graduates -- civil and electrical engineers mostly -- from the class of 2008. This year, says Liang Yi, the vice CEO of the CRCC subsidiary working on the Beijing-to-Shanghai high-speed line, the company may hire up to 20,000 new university grads to cope with the company's intensifying workload. But with the private sector cutting way back on hiring -- and university students desperate for work -- taking on that many new engineers and managers hasn't been too difficult.

It's been even less of a problem offering jobs to manual laborers on sites across the country. Liang says his unit alone is absorbing 8,000 more workers this year than it did last. It gives each one five days of basic safety training, which isn't a lot, but in China it's very rare for manual laborers to get any safety training. Says chief engineer Xia: "Yes, we have more pressure on us, but we're not doing anything we weren't doing before. We're just doing more of it."

The other key thing to remember is that China's brand-new high-speed rail network will be the product of the country's economic system. For all the free-market progress China has made in the past 30 years, a heavy "command and control" component still exists. The central government in Beijing holds all the key levers of power. The Railroad Ministry sets the plans, state-owned banks lend the money, and state-owned companies get the projects rolling. In the meantime many private businesses struggle to get bank loans.

Indeed, "command and control" is an especially fitting metaphor for the high-speed railway build-out. Until 1984 the Ministry of Railroads and what are now the construction companies were all part of China's People's Liberation Army. To this day, many of the senior and middle management ranks are made up of former army officers -- conservative executives who are very good at following orders.

The result is that when plans are made, they also get executed. In America, jokes Sean Maloney, the No. 3 executive at Intel, "NIMBY-ism [Not in My Backyard] is still an issue. In China, it's more like IMBY-ism. They plan, they build things, and they move fast."

Occasionally that can stir up trouble. A year and a half ago middle-class residents in a Shanghai neighborhood went public -- a relatively rare event in China -- with a protest against a high-speed rail line being built south to Hangzhou because it was too close to their homes. They created enough of a ruckus that Premier Wen Jiabao himself interceded and forced a change in the line's route.

Still, all things considered, in the midst of the grinding global recession, a little IMBY-ism doesn't seem like such a bad thing to some multinational companies. China's stimulus plan has taken some flak for what some critics perceive to be a "buy China" bias in its spending. But when it comes to the rail program, any number of big foreign players claim to be benefiting directly. Bombardier of Canada got the contract for a signaling system on the network as well as for work on 40 high-speed trains. Altogether, Fortune estimates that foreign companies have won some $10 billion worth of contracts so far, and in a program that extends to 2020, there's more where that came from.

IBM (IBM, Fortune 500) is among the companies aggressively pushing for a share of the historic build-out. It won a contract to provide the software for the high-speed train spur (as well as a local intracity rail system) in Guangdong province. High-speed rail systems are as much about silicon chips and software as about cement and steel. So-called smart train networks -- and the software systems that run them -- can boost on-time performance, speed up maintenance, and improve safety. And Big Blue, for its part, has already decided not only where the future is for this industry but also where the present is.

How so? Consider that the Northeast Corridor, between Boston and Washington, D.C., is served by Amtrak's Acela train, which clips along at a stately average speed of 79 miles an hour. There's a lot of talk now, as part of President Obama's stimulus plan, about upgrading the system and building new, faster lines all across the nation. In his stimulus bill Obama has allocated $8 billion over three years for high-speed rail, and 40 states are now bidding for the funds, with results to be released in September. Among the possibilities, California wants to link San Francisco with L.A. via a high-speed link. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) wants the private sector to get into the act, proposing a high-speed spur to connect Las Vegas with L.A.

Maybe, after environmental reviews are finished and eminent domain issues settled, those lines will be built. Meanwhile, IBM opened its new global high-speed-rail innovation center last month.

In Beijing.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org (great free site)